Sunday With Books: Cream

Since falling back in love with reading over the last few years, I’ve come to at least one inflexible conclusion about what it takes for a book to capture and maintain my interest:

In my eyes, a good book should never stops asking questions. Preferably it opens with one, something vague, mysterious, foggy. I like to be misled; if I get to the end of the book and realize I’ve been asking the wrong questions the entire time, that’s fine too. In fact, I think that’s my favorite kind of ending.

If you understand where I’m coming from with any of this, read on. I may have a new favorite for you.

His name is Haruki Murakami, and he’s arguably Japan’s greatest living writer. With Murakami, there’s always some kind of riddle, a ghostly intimation of some greater myth at play, one that is only hinted at, never disclosed in full. Think: Kafka without the mortal terror, Joyce without the celtic Jargon.

Below you’ll find his short story “Cream” in its entirety, taken from his latest collection First Person Singular. It’s a semi-autobiographical story based on an encounter Marukami had with an old man in a park sometime in his youth - which sounds boring, I’m aware; but give it a shot. In Marukami’s world, what is mundane and Earthly in one moment quickly becomes surreal and dreamlike in the next. He’s got a real knack for dealing in the metaphysical. —Jackson Todd

* * *

So I’m telling a younger friend of mine about a strange incident that took place back when I was eighteen. I don’t recall exactly why I brought it up. It just happened to come up as we were talking. I mean, it was something that happened long ago. Ancient history. On top of which, I was never able to reach any conclusion about it.

“I’d already graduated from high school then, but wasn’t in college yet,” I explained. “I was what’s called an academic ronin, a student who fails the university entrance exam and is waiting to try again. Things felt kind of up in the air,” I went on, “but that didn’t bother me much. I knew that I could get into a halfway decent private college if I wanted to. But my parents had insisted that I try for a national university, so I took the exam, knowing all along that it’d be a bust. And, sure enough, I failed. The national-university exam back then had a mandatory math section, and I had zero interest in calculus. I spent the next year basically killing time, as if I were creating an alibi. Instead of attending cram school to prepare to retake the exam, I hung out at the local library, plowing my way through thick novels. My parents must have assumed that I was studying there. But, hey, that’s life. I found it a lot more enjoyable to read all of Balzac than to delve into the principles of calculus.”

At the beginning of October that year, I received an invitation to a piano recital from a girl who’d been a year behind me in school and had taken piano lessons from the same teacher as I had. Once, the two of us had played a short four-hands piano piece by Mozart. When I turned sixteen, though, I’d stopped taking lessons, and I hadn’t seen her after that. So I couldn’t figure out why she’d sent me this invitation. Was she interested in me? No way. She was attractive, for sure, though not my type in terms of looks; she was always fashionably dressed and attended an expensive private girls’ school. Not at all the kind to fall for a bland, run-of-the-mill guy like me.

When we played that piece together, she gave me a sour look every time I hit a wrong note. She was a better pianist than I was, and I tended to get overly tense, so when the two of us sat side by side and played I bungled a lot of notes. My elbow bumped against hers a few times as well. It wasn’t such a difficult piece, and, moreover, I had the easier part. Each time I blew it, she had this Give me a break expression on her face. And she’d click her tongue—not loudly but loud enough that I could catch it. I can still hear that sound, even now. That sound may even have had something to do with my decision to give up the piano.

At any rate, my relationship with her was simply that we happened to study in the same piano school. We’d exchange hellos if we ran into each other there, but I have no memory of our ever sharing anything personal. So suddenly receiving an invitation to her recital (not a solo recital but a group recital with three pianists) took me completely by surprise—in fact, had me baffled. But one thing I had in abundance that year was time, so I sent off the reply postcard, saying that I would attend. One reason I did this was that I was curious to find out what lay behind the invitation—if, indeed, there was a motive. Why, after all this time, send me an unexpected invitation? Maybe she had become much more skilled as a pianist and wanted to show me that. Or perhaps there was something personal that she wished to convey to me. In other words, I was still figuring out how best to use my sense of curiosity, and banging my head against all kinds of things in the process.

The recital hall was at the top of one of the mountains in Kobe. I took the Hankyu train line as close as I could, then boarded a bus that made its way up a steep, winding road. I got off at a stop near the very top, and after a short walk arrived at the modest-sized concert venue, which was owned and managed by an enormous business conglomerate. I hadn’t known that there was a concert hall here, in such an inconvenient spot, at the top of a mountain, in a quiet, upscale residential neighborhood. As you can imagine, there were plenty of things in the world that I didn’t know about.

I’d felt that I should bring something to show my appreciation for having been invited, so at a florist’s near the train station I had selected a bunch of flowers that seemed to fit the occasion and had them wrapped as a bouquet. The bus had shown up just then and I’d hopped aboard. It was a chilly Sunday afternoon. The sky was covered with thick gray clouds, and it looked as though a cold rain might start at any minute. There was no wind, though. I was wearing a thin, plain sweater under a gray herringbone jacket with a touch of blue, and I had a canvas bag slung across my shoulder. The jacket was too new, the bag too old and worn out. And in my hands was this gaudy bouquet of red flowers wrapped in cellophane. When I got on the bus decked out like that, the other passengers kept glancing at me. Or maybe it just seemed as if they did. I could feel my cheeks turning red. Back then, I blushed at the slightest provocation. And the redness took forever to go away.

“Why in the world am I here?” I asked myself, as I sat hunched over in my seat, cooling my flushed cheeks with my palms. I didn’t particularly want to see this girl, or hear the piano recital, so why was I spending all my allowance on a bouquet, and travelling all the way to the top of a mountain on a dreary Sunday afternoon in November? Something must have been wrong with me when I dropped the reply postcard in the mailbox.

The higher up the mountain we went, the fewer passengers there were on the bus, and by the time we arrived at my stop only the driver and I were left. I got off the bus and followed the directions on the invitation up a gently sloping street. Each time I turned a corner, the harbor came briefly into view and then disappeared again. The overcast sky was a dull color, as if blanketed with lead. There were huge cranes down in the harbor, jutting into the air like the antennae of some ungainly creatures that had crawled out of the ocean.

The houses near the top of the slope were large and luxurious, with massive stone walls, impressive front gates, and two-car garages. The azalea hedges were all neatly trimmed. I heard what sounded like a huge dog barking somewhere. It barked loudly three times, and then, as if someone had scolded it severely, it abruptly stopped, and all around became quiet.

As I followed the simple map on the invitation, I was struck by a vague, disconcerting premonition. Something just wasn’t right. First of all, there was the lack of people in the street. Since getting off the bus, I hadn’t seen a single pedestrian. Two cars did drive by, but they were on their way down the slope, not up. If a recital was really about to take place here, I would have expected to see more people. But the whole neighborhood was still and silent, as if the dense clouds above had swallowed up all sound.

Had I misunderstood?

I took the invitation out of my jacket pocket to recheck the information. Maybe I’d misread it. I went over it carefully, but couldn’t find anything wrong. I had the right street, the right bus stop, the right date and time. I took a deep breath to calm myself, and set off again. The only thing I could do was get to the concert hall and see.

When I finally arrived at the building, the large steel gate was locked tight. A thick chain ran around the gate, and was held in place by a heavy padlock. No one else was around. Through a narrow opening in the gate, I could see a fair-sized parking lot, but not a single car was parked there. Weeds had sprouted between the paving stones, and the parking lot looked as if it hadn’t been used in quite some time. Despite all that, the large nameplate at the entrance told me that this was indeed the recital hall I was looking for.

I pressed the button on the intercom next to the entrance but no one responded. I waited a bit, then pressed the button again, but still no answer. I looked at my watch. The recital was supposed to start in fifteen minutes. But there was no sign that the gate would be opened. Paint had peeled off it in spots, and it was starting to rust. I couldn’t think of anything else to do, so I pressed the intercom button one more time, holding it down longer, but the result was the same as before—deep silence.

With no idea what to do, I leaned back against the gate and stood there for some ten minutes. I had a faint hope that someone else might show up before long. But no one came. There was no sign of any movement, either inside the gate or outside. There was no wind. No birds chirping, no dogs barking. As before, an unbroken blanket of gray cloud lay above.

I finally gave up—what else could I do?—and with heavy steps started back down the street toward the bus stop, totally in the dark about what was going on. The only clear thing about the whole situation was that there wasn’t going to be a piano recital or any other event held here today. All I could do was head home, bouquet of red flowers in hand. My mother would doubtless ask, “What’re the flowers for?,” and I would have to give some plausible answer. I wanted to toss them in the trash bin at the station, but they were—for me, at least—kind of expensive to just throw away.

Down the hill a short distance, there was a cozy little park, about the size of a house lot. On the far side of the park, away from the street, was an angled natural rock wall. It was barely a park—it had no water fountain or playground equipment. All that was there was a little arbor, plunked down in the middle. The walls of the arbor were slanted latticework, overgrown with ivy. There were bushes around it, and flat square stepping stones on the ground. It was hard to say what the park’s purpose was, but someone was regularly taking care of it; the trees and bushes were smartly clipped, with no weeds or trash around. On the way up the hill, I’d walked right by the park without noticing it.

I went into the park to gather my thoughts and sat down on a bench next to the arbor. I felt that I should wait in the area a little longer to see how things developed (for all I knew, people might suddenly appear), and once I sat down I realized how tired I was. It was a strange kind of exhaustion, as though I’d been worn out for quite a while but hadn’t noticed it, and only now had it hit me. From the arbor, there was a panoramic view of the harbor. A number of large container ships were docked at the pier. From the top of the mountain, the stacked metal containers looked like nothing more than the small tins that you keep on your desk to hold coins or paper clips.

After a while, I heard a man’s voice in the distance. Not a natural voice but one amplified by a loudspeaker. I couldn’t catch what was being said, but there was a pronounced pause after each sentence, and the voice spoke precisely, without a trace of emotion, as if trying to convey something extremely important as objectively as possible. It occurred to me that maybe this was a personal message directed at me, and me alone. Someone was going to the trouble of telling me where I’d gone wrong, what it was that I’d overlooked. Not something I would normally have thought, but for some reason it struck me that way. I listened carefully. The voice got steadily louder and easier to understand. It must have been coming from a loudspeaker on the roof of a car that was slowly wending its way up the slope, seemingly in no hurry at all. Finally, I realized what it was: a car broadcasting a Christian message.

“Everyone will die,” the voice said in a calm monotone. “Every person will eventually pass away. No one can escape death or the judgment that comes afterward. After death, everyone will be severely judged for his sins.”

I sat there on the bench, listening to this message. I found it strange that anyone would do mission outreach in this deserted residential area up on top of a mountain. The people who lived here all owned multiple cars and were affluent. I doubted that they were seeking salvation from sin. Or maybe they were? Income and status might be unrelated to sin and salvation.

“But all those who seek salvation in Jesus Christ and repent of their sins will have their sins forgiven by the Lord. They will escape the fires of Hell. Believe in God, for only those who believe in Him will reach salvation after death and receive eternal life.”

I was waiting for the Christian-mission car to appear on the street in front of me and say more about the judgment after death. I think I must have been hoping to hear words spoken in a reassuring, resolute voice, no matter what they were. But the car never showed up. And, at a certain point, the voice began to grow quieter, less distinct, and before long I couldn’t hear anything anymore. The car must have turned in another direction, away from where I was. When that car disappeared, I felt as though I’d been abandoned by the world.

Asudden thought hit me: maybe the whole thing was a hoax that the girl had cooked up. This idea—or hunch, I should say—came out of nowhere. For some reason that I couldn’t fathom, she’d deliberately given me false information and dragged me out to the top of a remote mountain on a Sunday afternoon. Maybe I had done something that had caused her to form a personal grudge against me. Or maybe, for no special reason, she found me so unpleasant she couldn’t stand it. And she’d sent me an invitation to a nonexistent recital and was now gloating—laughing her head off—seeing (or, rather, imagining) how she’d fooled me and how pathetic and ridiculous I must look.

O.K., but would a person really go to all the trouble of coming up with such a complicated plot in order to harass someone, just out of spite? Even printing up the postcard must have taken some effort. Could someone really be that mean? I couldn’t remember a thing I’d ever done to make her hate me that much. But sometimes, without even realizing it, we trample on people’s feelings, hurt their pride, make them feel bad. I speculated on the possibility of this not unthinkable hatred, the misunderstandings that might have taken place, but found nothing convincing. And as I wandered fruitlessly through this maze of emotions I felt my mind losing its way. Before I knew it, I was having trouble breathing.

This used to happen to me once or twice a year. I think it must have been stress-induced hyperventilation. Something would fluster me, my throat would constrict, and I wouldn’t be able to get enough air into my lungs. I’d panic, as if I were being swept under by a rushing current and were about to drown, and my body would freeze. All I could do at those times was crouch down, close my eyes, and patiently wait for my body to return to its usual rhythms. As I got older, I stopped experiencing these symptoms (and, at some point, I stopped blushing so easily, too), but in my teens I was still troubled by these problems.

On the bench by the arbor, I screwed my eyes tightly shut, bent over, and waited to be freed from that blockage. It may have been five minutes, it may have been fifteen. I don’t know how long. All the while, I watched as strange patterns appeared and vanished in the dark, and I slowly counted them, trying my best to get my breathing back under control. My heart beat out a ragged tempo in my rib cage, as if a terrified mouse were racing about inside.

I’d been focussing so much on counting that it took some time for me to become aware of the presence of another person. It felt as if someone were in front of me, observing me. Cautiously, ever so slowly, I opened my eyes and raised my head a degree. My heart was still thumping.

Without my noticing, an old man had sat down on the bench across from me and was looking straight at me. It isn’t easy for a young man to judge an elderly person’s age. To me, they all just looked like old people. Sixty, seventy—what was the difference? They weren’t young anymore, that was all. This man was wearing a bluish-gray wool cardigan, brown corduroy pants, and navy-blue sneakers. It looked as though a considerable amount of time had passed since any of these were new. Not that he appeared shabby or anything. His gray hair was thick and stiff-looking, and tufts sprung up above his ears like the wings of birds when they bathe. He wasn’t wearing glasses. I didn’t know how long he’d been there, but I had the feeling that he’d been observing me for quite some time.

I was sure he was going to say, “Are you all right?,” or something like that, since I must have looked as if I were having trouble (and I really was). That was the first thing that sprang to mind when I saw the old man. But he didn’t say a thing, didn’t ask anything, just gripped a tightly folded black umbrella that he was holding like a cane. The umbrella had an amber-colored wooden handle and looked sturdy enough to serve as a weapon if need be. I assumed that he lived in the neighborhood, since he had nothing else with him.

I sat there trying to calm my breathing, the old man silently watching. His gaze didn’t waver for an instant. It made me feel uncomfortable—as if I’d wandered into someone’s back yard without permission—and I wanted to get up from the bench and head off to the bus stop as fast as I could. But, for some reason, I couldn’t get to my feet. Time passed, and then suddenly the old man spoke.

“A circle with many centers.”

I looked up at him. Our eyes met. His forehead was extremely broad, his nose pointed. As sharply pointed as a bird’s beak. I couldn’t say a thing, so the old man quietly repeated the words: “A circle with many centers.”

Naturally, I had no clue what he was trying to say. A thought came to me—that this man had been driving the Christian loudspeaker car. Maybe he’d parked nearby and was taking a break? No, that couldn’t be it. His voice was different from the one I’d heard. The loudspeaker voice was a much younger man’s. Or perhaps that had been a recording.

“Circles, did you say?” I reluctantly asked. He was older than me, and politeness dictated that I respond.

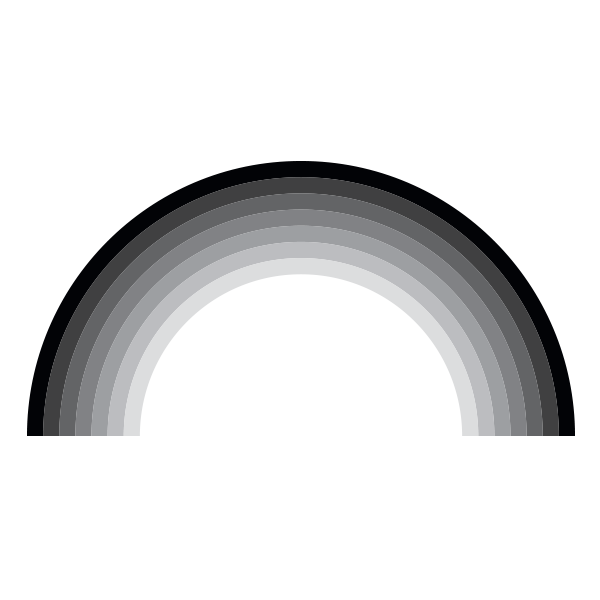

“There are several centers—no, sometimes an infinite number—and it’s a circle with no circumference.” The old man frowned as he said this, the wrinkles on his forehead deepening. “Are you able to picture that kind of circle in your mind?”

My mind was still out of commission, but I gave it some thought. A circle that has several centers and no circumference. But, think as I might, I couldn’t visualize it.

“I don’t get it,” I said.

The old man silently stared at me. He seemed to be waiting for a better answer.

“I don’t think they taught us about that kind of circle in math class,” I feebly added.

The old man slowly shook his head. “Of course not. That’s to be expected. Because they don’t teach you that kind of thing in school. As you know very well.”

As I knew very well? Why would this old man presume that?

“Does that kind of circle really exist?” I asked.

“Of course it does,” the old man said, nodding a few times. “That circle does indeed exist. But not everyone can see it, you know.”

“Can you see it?”

The old man didn’t reply. My question hung awkwardly in the air for a moment, and finally grew hazy and disappeared.

The old man spoke again. “Listen, you’ve got to imagine it with your own power. Use all the wisdom you have and picture it. A circle that has many centers but no circumference. If you put in such an intense effort that it’s as if you were sweating blood—that’s when it gradually becomes clear what the circle is.”

“It sounds difficult,” I said.

“Of course it is,” the old man said, sounding as if he were spitting out something hard. “There’s nothing worth getting in this world that you can get easily.” Then, as if starting a new paragraph, he briefly cleared his throat. “But, when you put in that much time and effort, if you do achieve that difficult thing it becomes the cream of your life.”

“Cream?”

“In French, they have an expression: crème de la crème. Do you know it?”

“I don’t,” I said. I knew no French.

“The cream of the cream. It means the best of the best. The most important essence of life—that’s the crème de la crème. Get it? The rest is just boring and worthless.”

I didn’t really understand what the old man was getting at. Crème de la crème?

“Think about it,” the old man said. “Close your eyes again, and think it all through. A circle that has many centers but no circumference. Your brain is made to think about difficult things. To help you get to a point where you understand something that you didn’t understand at first. You can’t be lazy or neglectful. Right now is a critical time. Because this is the period when your brain and your heart form and solidify.”

I closed my eyes again and tried to picture that circle. I didn’t want to be lazy or neglectful. But, no matter how seriously I thought about what the man was saying, it was impossible for me at that time to grasp the meaning of it. The circles I knew had one center, and a curved circumference connecting points that were equidistant from it. The kind of simple figure you can draw with a compass. Wasn’t the kind of circle the old man was talking about the opposite of a circle?

I didn’t think that the old man was off, mentally. And I didn’t think that he was teasing me. He wanted to convey something important. So I tried again to understand, but my mind just spun around and around, making no progress. How could a circle that had many (or perhaps an infinite number of) centers exist as a circle? Was this some advanced philosophical metaphor? I gave up and opened my eyes. I needed more clues.

But the old man wasn’t there anymore. I looked all around, but there was no sign of anyone in the park. It was as if he’d never existed. Was I imagining things? No, of course it wasn’t some fantasy. He’d been right there in front of me, tightly gripping his umbrella, speaking quietly, posing a strange question, and then he’d left.

I realized that my breathing was back to normal, calm and steady. The rushing current was gone. Here and there, gaps had started to appear in the thick layer of clouds above the harbor. A ray of light had broken through, illuminating the aluminum housing on top of a crane, as if it had been accurately aiming at that one spot. I stared for a long while, transfixed by the almost mythic scene.

The small bouquet of red flowers, wrapped in cellophane, was beside me. Like a kind of proof of all the strange things that had happened to me. I debated what to do with it, and ended up leaving it on the bench by the arbor. To me, that seemed the best option. I stood up and headed toward the bus stop where I’d got off earlier. The wind had started blowing, scattering the stagnant clouds above.

After I finished telling this story, there was a pause, then my younger friend said, “I don’t really get it. What actually happened, then? Was there some intention or principle at work?”

Those very odd circumstances I experienced on top of that mountain in Kobe on a Sunday afternoon in late autumn—following the directions on the invitation to where the recital was supposed to take place, only to discover that the building was deserted—what did it all mean? And why did it happen? That was what my friend was asking. Perfectly natural questions, especially because the story I was telling him didn’t reach any conclusion.

“I don’t understand it myself, even now,” I admitted.

It was permanently unsolved, like some ancient riddle. What took place that day was incomprehensible, inexplicable, and at eighteen it left me bewildered and mystified. So much so that, for a moment, I nearly lost my way.

“But I get the feeling,” I said, “that principle or intention wasn’t really the issue.”

My friend looked confused. “Are you telling me that there’s no need to know what it was all about?”

I nodded.

“But if it were me,” he said, “I’d be bothered no end. I’d want to know the truth, why something like that happened. If I’d been in your shoes, that is.”

“Yeah, of course. Back then, it bothered me, too. A lot. It hurt me, too. But thinking about it later, from a distance, after time had passed, it came to feel insignificant, not worth getting upset about. I felt as though it had nothing at all to do with the cream of life.”

“The cream of life,” he repeated.

“Things like this happen sometimes,” I told him. “Inexplicable, illogical events that nevertheless are deeply disturbing. I guess we need to not think about them, just close our eyes and get through them. As if we were passing under a huge wave.”

My younger friend was quiet for a time, considering that huge wave. He was an experienced surfer, and there were lots of things, serious things, that he had to consider when it came to waves. Finally, he spoke. “But not thinking about anything might also be pretty hard.”

“You’re right. It might be hard indeed.”

There’s nothing worth getting in this world that you can get easily, the old man had said, with unshakable conviction, like Pythagoras explaining his theorem.

“About that circle with many centers but no circumference,” my friend asked. “Did you ever find an answer?”

“Good question,” I said. I slowly shook my head. Had I?

In my life, whenever an inexplicable, illogical, disturbing event takes place (I’m not saying that it happens often, but it has a few times), I always come back to that circle—the circle with many centers but no circumference. And, as I did when I was eighteen, on that arbor bench, I close my eyes and listen to the beating of my heart.

Sometimes I feel that I can sort of grasp what that circle is, but a deeper understanding eludes me. This circle is, most likely, not a circle with a concrete, actual form but, rather, one that exists only within our minds. When we truly love somebody, or feel deep compassion, or have an idealistic sense of how the world should be, or when we discover faith (or something close to faith)—that’s when we understand the circle as a given and accept it in our hearts. Admittedly, though, this is nothing more than my own vague attempt to reason it out.

Your brain is made to think about difficult things. To help you get to a point where you understand something that you didn’t understand at first. And that becomes the cream of your life. The rest is boring and worthless. That was what the gray-haired old man told me. On a cloudy Sunday afternoon in late autumn, on top of a mountain in Kobe, as I clutched a small bouquet of red flowers. And even now, whenever something disturbing happens to me, I ponder again that special circle, and the boring and the worthless. And the unique cream that must be there, deep inside me.

[above photo by Shomei Tomatsu]